Interview with Mark Griffiths by Caroline Lamb – November 2025

It’s approaching the end of November when I catch up with EVAN member Mark Griffiths. The Penrith Sparkle event - including the switching on of the Christmas lights and the town’s famous Droving parade - is due to take place the following day, but the grim and drizzly weather is holding off for now!

I’ve travelled in on the train this morning, which always feels like something of a risk these days - but I’ve planned well around the inevitable delays so, fortunately, timings are good and casual as I reach the gallery at 4, Corney Place.

Mark arrives and the meeting feels warm and animated. We settle down in a pair of chairs amidst the diverse and striking artworks on display around the entranceway.

To many creatives - myself included! - openly discussing craft and inspiration can feel exposing and often uncomfortable. However, Mark doesn’t seem to struggle at all. He’s enthusiastic and unguarded from the off, and conversation flows so naturally that I all but abandon the template questions I’ve prepared, as there’s next to no need for them! I simply start recording as we fall into an easy chat.

He’s not long returned from Gdańsk - a place that has ingrained itself permanently into his psyche. He’s brought along transfixing printed images captured during his explorations of the Polish port city, struck through with great arms of cranes, looming edifices of brutalist industrial architecture and bold, disruptive but beautiful street art.

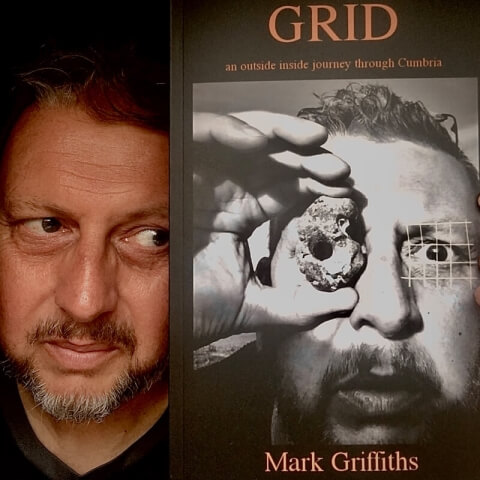

It's clear that Mark is partial to work that can be collected together and held in one’s hands. He’s also brought his wonderful 2021 publication, Grid - a set of site-specific poems, songs, prose and images concerning Cumbria and the Lake District - as well as a number of folders containing further writings, prints, paintings and illustrations.

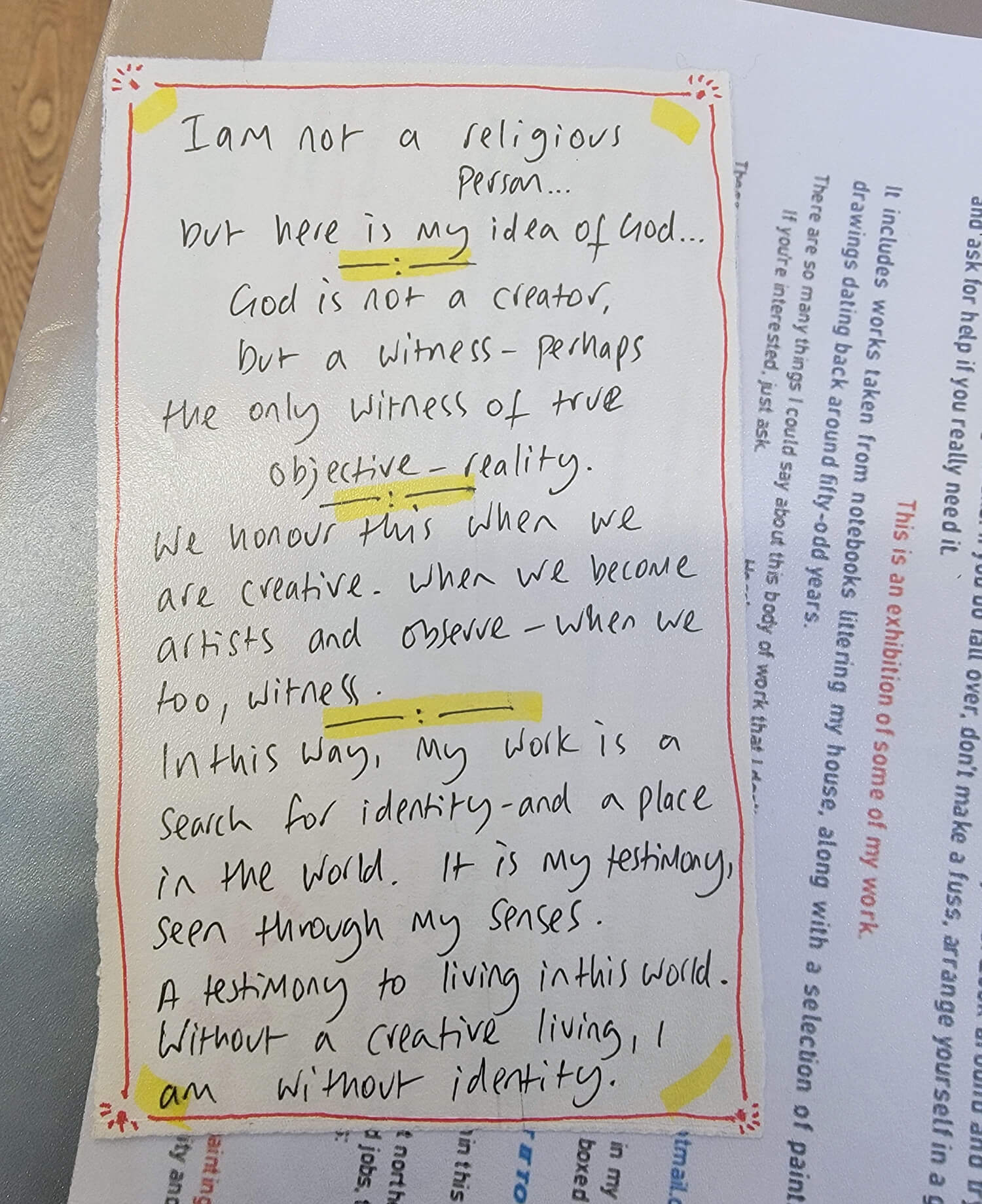

“I've got a thousand and one sketchbooks and notebooks that I've always kept since being a child.” Mark says. “We were working on the house a couple of years ago and I was sort of moving everything and reviewing things. And I thought: the sketchbooks are the best part of me. The most interesting part; not in a diary sense, particularly - but, I suppose, in an artistic evolutionary sense. They also contain the genesis of all the poetry.”

He has another book on the way that has been waiting for two years on the sidelines. “I've got too much material. I'm daunted by it now, and I'm just at the stage where, because life's so busy, I know there's this book that needs writing, or needs editing and putting together - all the boring stuff… and I can feel it there now.”

I think that Mark’s preference for creating collections comes from a place of compartmentalism, at least to some degree. "It's a cleansing process when you produce something, whether it's an exhibition or a book, because you're clearing the decks - and it's gone, it's fixed, because it's in print. There's a permanence to that. And you might go back and re-read it and think ‘Oh, I should have changed that’. But no, I've made my bed. I lie in it.

It's years of work to make a collection. From the odd survivor from when you were sixteen and full of angst that just makes it through the quality control process. Then, of course, once completed, you've got to start again. And it's like being married for a long time and then going into another relationship - and all your stories are about another person. Suddenly, you have to think: ‘Ah, we're going to have to create a new life and new stories’, which is liberating, I think.”

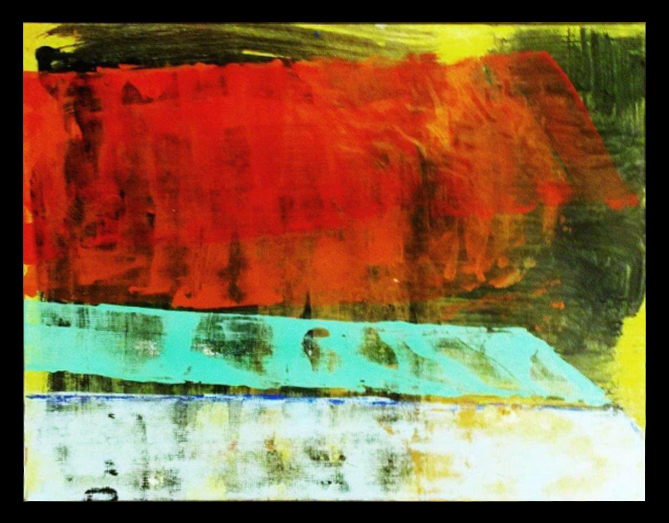

Mark is a polymath. He writes, draws, paints, makes music and more. “It's great,” he says “because you drive from one location and you go to another. Very often, you'll start a poem at the end of a song. Or even as a painting. Everything cross-references.”

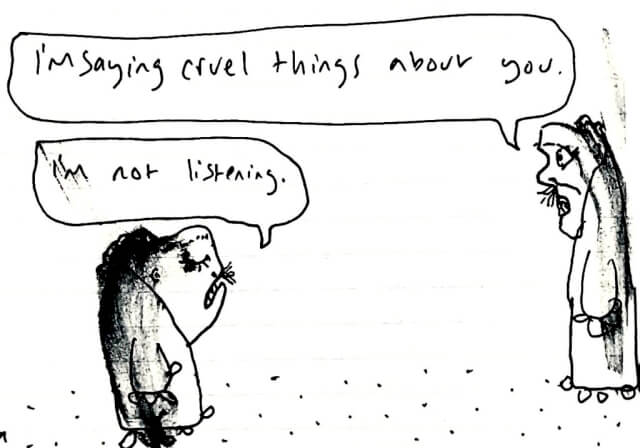

His prolific portfolio is bold and often undercut with unique social reflection, honesty and left-field humour. From hilarious R-rated Christmas cards and comic art (the first work he sold was a comic strip at school) to unconventional abstracts in bold colours, unapologetic statements and flowing poetry that seems sourced from instinct as much as practice, it begs to be studied and explored rather than just observed.

He believes that his work has no single theme or focus other than “a reaction to living”.

In his previous career - his “contracted work” as he calls it - much of his employment involved social responsibility. That reflects strongly in the pieces he continues to create. While he started out in maintenance in a factory, cleaning boilers and fixing pipes, he’s since worked for a number of charities in various locations across the UK; often in key positions. He’s been involved in outdoor, adventure and play therapy.

He has a deep sense of the importance of creative play - both in the making of art and in the development of good health and well-being.

Thinking back to his more recent work with children living with trauma, Mark says “I did a lot of work making stories. We'd start off and just play. If they had a carpet that looked like a road, we'd play cars - and move on from there and establish that trust, and then establish different dialogues. All the work - any creative pursuit I was involved in - fed into that last five years.”

He’s also taught art in colleges, and has seen a marked change in the approach to creativity within academic settings. “I've always had a lot of faith in the value of an art education.” He says. “I went to Rochdale College of Art, which at the time was, I think, one of the best foundation courses in the country.

They were doing some really good things. Joseph Beuys for example, was a great influence, along with radical, cutting-edge artists - and a lot of women's art. So I was being bashed around by a lot of new, radical ideas.

Even to students who were fresh out of school, they'd say ‘You're an artist!’ You were being told: ‘Come here, you're an artist - we'll treat you as an artist,’ there are expectations. I mean, it was a time when there was a bit of money, and you were working on large canvases at an early age. There was a brilliant sculpture studio, a foundry and things like this.”

A great number of Mark’s formative experiences with art can be traced back to this time.”

“I'd been there a couple of weeks,” he says “and there was Jeff Nuttall, who was a famous sort of doyen of the Northern arts scene. A strange, difficult man. He came to do a performance, and there was him and another guy, and they were wrestling about in overcoats - and were then revealed to be naked. One of the teachers said to me, ‘What do you think?’. I said ‘I like it, but I don't know why I like it!’”

The college had a Kurt Schwitters exhibition in the gallery at the same time. “It was the same again:” says Mark. “I liked it, but I didn't know why - and it was like ‘Don't worry about it, you will’. There was a lot of Zen-like teaching, you know. Art schools were full of frivolous ideas and silliness and the opportunity to test things out and unleash yourself. And later, many became places where you learned to design telephones and products.”

Mark says that, after leaving college, his own time teaching art was great “Because you got paid loads! They'd give you studio space and then you'd tour around the studios and talk to people about art. It's like ‘Kill me now: this is as good as it's going to get!’. What I noticed in later days was that art students were changing, or the people selected. Firstly, they had more money - and secondly, they had a real sense of a career path.

I think what happens when creativity becomes corporatised, is that the interesting stuff slips underground and elsewhere into other forms. Music was certainly a massive thing, because we were world-leading in terms of our subcultures and music cultures. With kids doing it themselves without formal training. Mark had been one of those kids.”

“I played my first gig at 14 at a Silver Jubilee street party. Me and the other 14-year-olds had formed a heavy metal band. And I didn't like heavy metal, but they were the only people to play with! I always loved jazz, because my dad was a jazz saxophonist. We had this band called Bomber, and we’d got two songs and we thought ‘We'll just have to play these twice’, you know?

So we played the first song at this street party and then this old bloke came up and said “I think that's enough now, lads”.

A member of EVAN for around a year at the time of our meeting, Mark has become involved in the group’s musical arm, the Eden Valley Touring Network, which organises a series of gigs across local venues in Cumbria, from winter into spring. His act - Mark Griffiths and the Word - combines music and poetry.

He’s not a pub-gigger. His performances need a listening audience, which means the Touring Network works perfectly for him. In fact, a major drive behind his joining EVAN in the first place was a wish to land more gigs.

“I'm lazy when it comes to things like that”, he says. “People say ‘you need a kick up the arse. You need to go and perform things’. Because I love doing it. It's fun. I talk a lot. I don't know what I'm going to play most of the time. I have a vague idea of the set list, but then I can go anywhere!”

Having the presence of EVAN in his life helps him to get out there and perform his work - and also facilitates collaboration with other talented creatives.

Mark’s relationship with music runs just as deep as his visual art, songwriting and poetry - and his experiences in the field have been just as eclectic, adventurous and rewarding. “I had a project in the Ribble Valley for a few years”, he says “- and this was the time of grunge and so on - and we set up a band in every village. They got kids at thirteen, fourteen, fifteen… there's absolutely nothing to do. There's a dearth of resources unless you're a farmer.”

The project even got funding to go to Glastonbury - which Mark describes as “the single best piece of work I've ever had.” This was back when there was money, he says.

“It was the year that Oasis first appeared. They had a smaller stage. And it was like ‘Right, we're going to meet here. Every two hours we'll meet here’. But what an experience it was. It was great to be able to do that work with young people. I love it when kids work on cars and things and they've got a passion.”

Mark’s enthusiasm and vibrant turn of phrase clearly show that, despite those days of “contracted work” now being behind him, the same passion still runs through him like a torrent. He cares deeply for the human side of being; the importance of close connections, for golden moments with family.

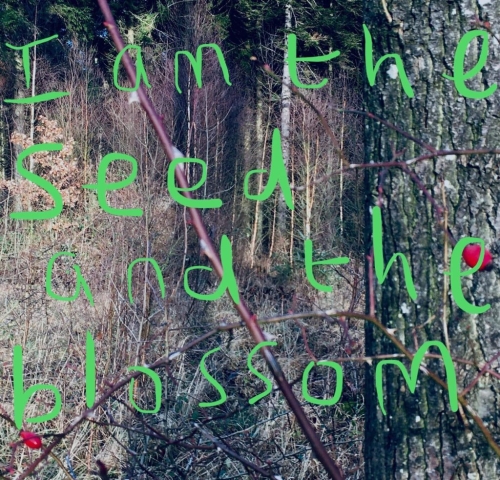

Light inspires him, he says, as a vehicle provoking and capturing mood. The idea he plans for the book he is currently preparing, is something of an exploration of light and darkness in mood, theme, deed and narrative and will end with a poem titled “The Light”, which “Describes the fallouts you have within families over the years, but how, ultimately, we're all sort of fishing in it. Fishing in the light of the sun as we're brought out of it.”

He is equally affected by the atmosphere of place; whether that place is the astonishing landscape on his doorstep in the Penrith area or somewhere further afield.

“In some ways, we're blessed in this country”, he says, “because we have light like we have today”. I look outside through the big gallery window. I’ve barely paid attention to the light; I’d just been glad it wasn’t raining yet!

“You have those hard edges and the colour suddenly vibrates.” says Mark. “You have the rain in autumn, where the mosses take on a life of their own. You have the grey slab gunmetal skies that soak up all the light, but then it might break through at four in the afternoon - and you get a gloaming - and suddenly everything vibrates again with an intensity.”

With the subject of the conversation shifting to the physical environment, we return to Mark’s visits to Gdańsk. “A lot of the former Eastern Bloc countries are really interesting to see. You've got the old cities, where the first shots of the Second World War were fired - so there's this incredible modern history. Then the shipyard. I can remember when I was a kid, about fourteen, fifteen, growing up with the news reports of the Solidarity movement in Gdańsk shipyards; they were so historic. It was communist rule then, and it was really the start of the end of communism and the old Soviet state. The shipyard had big riots and they shot and incarcerated the shipyard workers. And the shipyards are still there.”

He illustrates this with the astonishing images he’s brought along in one of his folders, that almost suck one into the cold midst of the industrial landscape he describes.

“In the old warehouses and yards, artists have moved in. The art that they're producing is phenomenal. They've got all those bits of old ships that they use, so it's quite monumental. It's really, really strong art. It's quite political, but at the same time very accessible and aesthetically strong.”

He lets me flip through the images. I wish I had more time; I wanted to take in as many as possible!

“They've got a massive estate of brutalist architecture from the communist era. It's called Zaspa. It's quite a famous place now. There are fourteen or fifteen-storey buildings with huge murals on the sides of them. Just big old murals, and you can tour around and walk among them.

They're not upper-class properties. It's not expensive housing, it's still cheap housing. But there's all this art there. It's such an atmospheric place. It's great to visit at this time of year.

And you've got the beautiful sort of tourist stuff, but then you've got this really rich history, modern history - so much that I can remember.”

His fascination with this collision of social history and art is certainly something I share, and I feel a renewed sense of it as I listen now. However, eventually, I’m forced by time to bring our conversation to an end. Mark and I are still chatting as we step out of the gallery to go about our days.

As I make my way towards the town centre once again, leaving behind the multifaceted flow of the last hour or so, I find myself taking in the shape and impact of the buildings around me - trying to place them within the map of Penrith’s own social history - and absorbing the quality of the light with far more zeal than before.

Mark's book "Grid" an outside inside journey through Cumbria, is available from Books Cumbria, priced just £8/

‘Grid’ is a collection of site-specific poems, songs, prose and images concerning Cumbria and the Lake District. It is the artist’s meditations on his life-long relationship with this part of North-West England, and it offers a thoughtful companion for all who feel a strong sense of place and fraternity with the landscape.